Over the past four years I have been gathering images and stories of – among many other things – garments that are shared. This has been part of Local Wisdom, a fashion research project exploring satisfying and resourceful ways of using clothes. Sharing – one of a broad suite of mechanisms of collaborative consumption (others include swapping, bartering, trading or renting access to products) – happens more often than we think. There will be very few among us who will not have borrowed a garment from a flatmate or sibling or who don’t have things that are shared through the generations, transferring their ownership as pieces are handed down within families and between friends.

Sharing makes sense in resource terms because one product can meet many people’s needs: we get more from less, more utility from fewer materials. Socially too, sharing also seems to enrich us, adding to our experience of clothes. Local Wisdom has captured stories of a husband and wife who share jumpers and shoes; six women from three generations of the same family who wear the same dress; and many other pieces whose sharing reinforces bonds and joint identity between the sharers, allowing us to gain access not just to more and different pieces but also to the values, histories and fashion expression of the owner.

So it would seem that promoting longitudinal sharing (passing down through generations to new owners) and latitudinal sharing (multiple users at one time) is a sustainability no brainer: it can help connect us to each other and to bigger environmental debates of resourcefulness. And yet it seems like many fashion and clothing brands, in a move which reflects both cultural conditions and today’s political economy, make a series of decisions, the effect of which is to actively reduce the likelihood of sharing and so lead us on a path away from sustainability.

If we can unclamp our imaginations and recognise that creating products which foster long term value in society more broadly actually benefits our businesses, then maybe we will stop sabotaging our sector’s prospects for sustainability

Ironically this happens at the same time as these same brands make overtures towards environmental protection typically through the pursuit of production efficiency. They substitute promising materials for damaging ones and pursue a ‘quality’ and recycling agenda. But they fail to realise that the way that people use their clothes offers potential to transform their brand’s sustainability profile in ways that a single-minded focus on materials and production never will.

Take the example of the Norwegian sportswear industry. Up until 2010 children’s sports clothing was mainly sold as unisex, its colour palette and fit largely androgynous. Then in 2010 this changed. Garments were designed in pink or blue and a gender dividing line was created in-store. Pretty much instantly sharing within families and between sexes was undermined. Garments became gender scripted and sharing potential restricted by half. Any hard-won gains with production efficiency were not just wiped out, but reversed at speed.

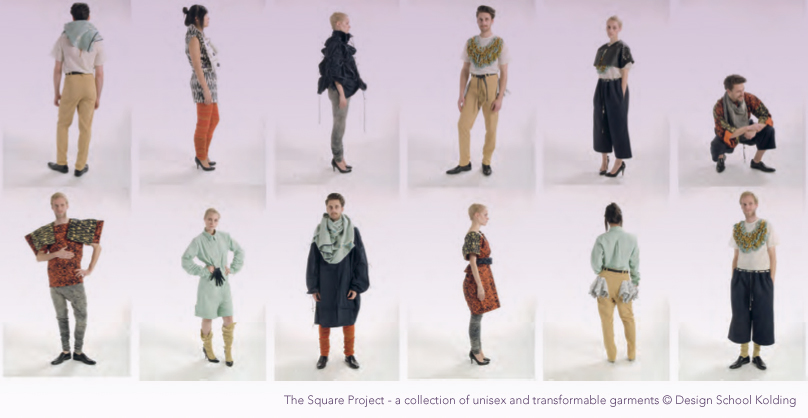

Certainly this raises many questions – including perhaps the most obvious and eternal one – why? The answer is complex and tied to, among other things, the economic logic of growth that seeks to open up new markets and intensify consumption rates in existing ones. It should also be understood against a backdrop of an already very substantial increase in sportswear consumption over the last 10 years, fuelled by increasing specialisation; a well known escalator of consumption. It seems like we are never satisfied – we find it hard to figure out how much is enough. Yet if we can unclamp our imaginations and recognise that creating products which foster long term value in society more broadly (such as sharing) actually benefits our businesses (because our businesses are dependent on a vital, flourishing society), then maybe we will stop sabotaging our sector’s prospects for sustainability. This is about seeing economic value as contingent on social value. Many people recognise the wisdom of this approach and design adaptable garments with inclusive scripts of use: unisex, unisize, multifunction, multiusers, trans-season etc. It is time we created value differently. Intensify and energise the process of use, not the practice of consumption.

Click here to find out more about how to cite this blog.

*The Square Project – a collection of unisex and transformable garments created by Anna Ebbesen, Benedicte Holmboe, Elin Sjøgren, Ruth Enoksen, Siff Nielsen,Tina Gabrijelcic and Mette Gliemann from Design School Kolding.